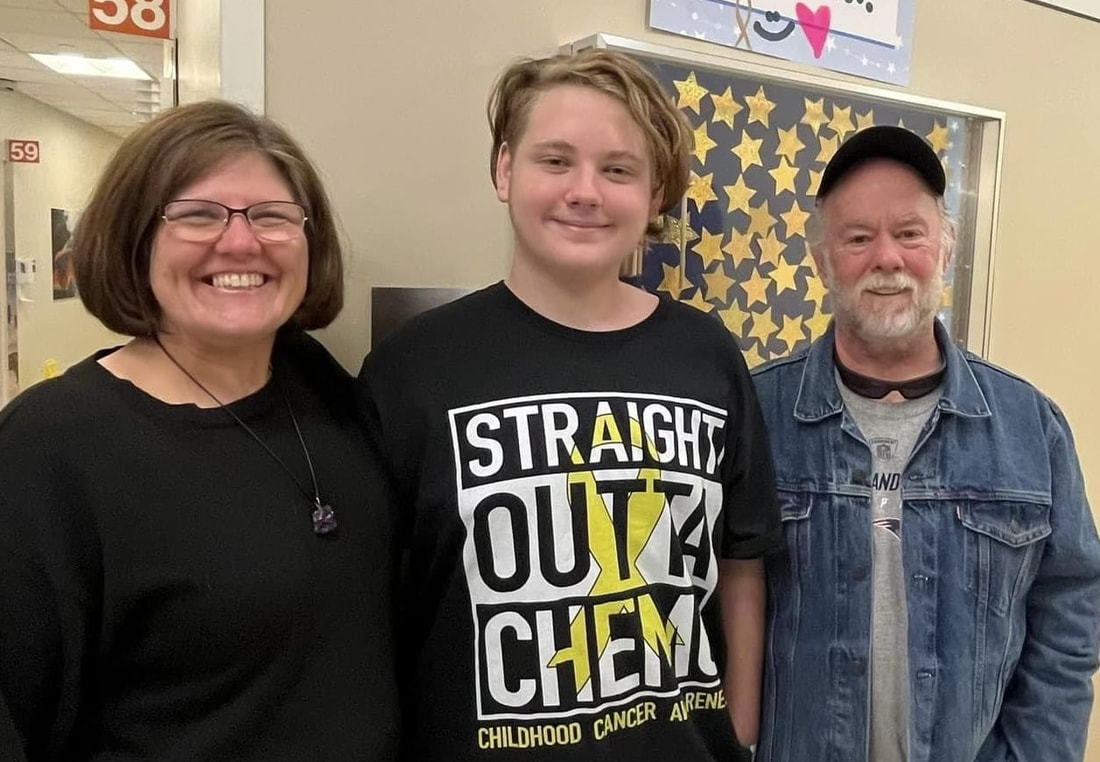

How Brady Beat Cancer with Better TreatmentThree years after 14-year-old Brady learned he had cancer, he and his parents reflect on their family’s journey and the opportunity to join the Children’s Oncology Group’s effort to bring less toxic treatments to patients. This is Brady’s larotrectinib story.

ALL PHOTOS COURTESY OF BRADY'S FAMILY

Brady is a 14-year-old anime fan, and a gamer who loves nothing more than to play games on his Xbox. He dreams of becoming a YouTuber (his dream) or maybe an engineer (a solid plan B per his mom).

|

Brady is also one of the kids whose participation in the Children’s Oncology Group (COG)-sponsored clinical trial for the targeted therapy larotrectinib means he is now living cancer-free.

Reflecting on what it was like to participate in the COG trial, Brady said, “It feels good to know more kids might have the same opportunity to get treated with larotrectinib – and not have to lose their hair and feel sick all the time.”

Reflecting on what it was like to participate in the COG trial, Brady said, “It feels good to know more kids might have the same opportunity to get treated with larotrectinib – and not have to lose their hair and feel sick all the time.”

|

The mystery bump

In October 2021, Brady needed a new dress shirt to attend his sister's wedding rehearsal dinner. As he, his mom Stacy, and dad Doug were standing in line to buy a new shirt, Brady lifted his chin at an angle and his mom asked, "What’s that bump on your neck?" The bump was the size of a small tangerine. “A few weeks before, Brady was getting very winded walking – and coughing. We thought it was asthma, which he had when he was younger,” said Stacy. |

Brady’s doctor wondered about swollen lymph nodes. But the lump was only on one side. In need of a more precise explanation, Stacy drove Brady to the ER.

A CT scan in the ER showed a severely blocked windpipe. Instead of being the shape of a full moon, Brady’s windpipe was compressed – likely by a tumor – into the shape of a crescent moon.

The emergency medicine team wanted to transfer him to a children's hospital with the expertise Brady needed to be treated for what the team was worried was cancer. Stacy assumed she and Brady would ride to a nearby hospital in an ambulance – together. Instead, the team told her, “We need to airlift him in a helicopter to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), in case he needs emergency surgery to open his windpipe. You can’t go with him because of COVID protocols and limited space. You’ll need to go in your car.”

Stacy’s phone said the trip would take two hours. But Stacy and Doug arrived in exactly 1 hour and 37 minutes – their own version of flying.

A CT scan in the ER showed a severely blocked windpipe. Instead of being the shape of a full moon, Brady’s windpipe was compressed – likely by a tumor – into the shape of a crescent moon.

The emergency medicine team wanted to transfer him to a children's hospital with the expertise Brady needed to be treated for what the team was worried was cancer. Stacy assumed she and Brady would ride to a nearby hospital in an ambulance – together. Instead, the team told her, “We need to airlift him in a helicopter to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), in case he needs emergency surgery to open his windpipe. You can’t go with him because of COVID protocols and limited space. You’ll need to go in your car.”

Stacy’s phone said the trip would take two hours. But Stacy and Doug arrived in exactly 1 hour and 37 minutes – their own version of flying.

|

The waiting game

The next day, the oncology team at CHOP did a biopsy of the lump. They told Stacy and Doug, "We'll have the results in about two days. Once we know what it is, we can figure out what the next steps are." The team of doctors initially thought Brady had a type of thyroid cancer, but the biopsy showed something different – a rare tumor called a spindle cell neoplasm. They needed more time to run specialized genetic testing on the tumor to better understand what type of cancer it was so they could make the best plan to treat it. |

Given how the tumor was compressing Brady’s airway, the team decided to send his biopsy to an out-of-state lab that could expedite the results.

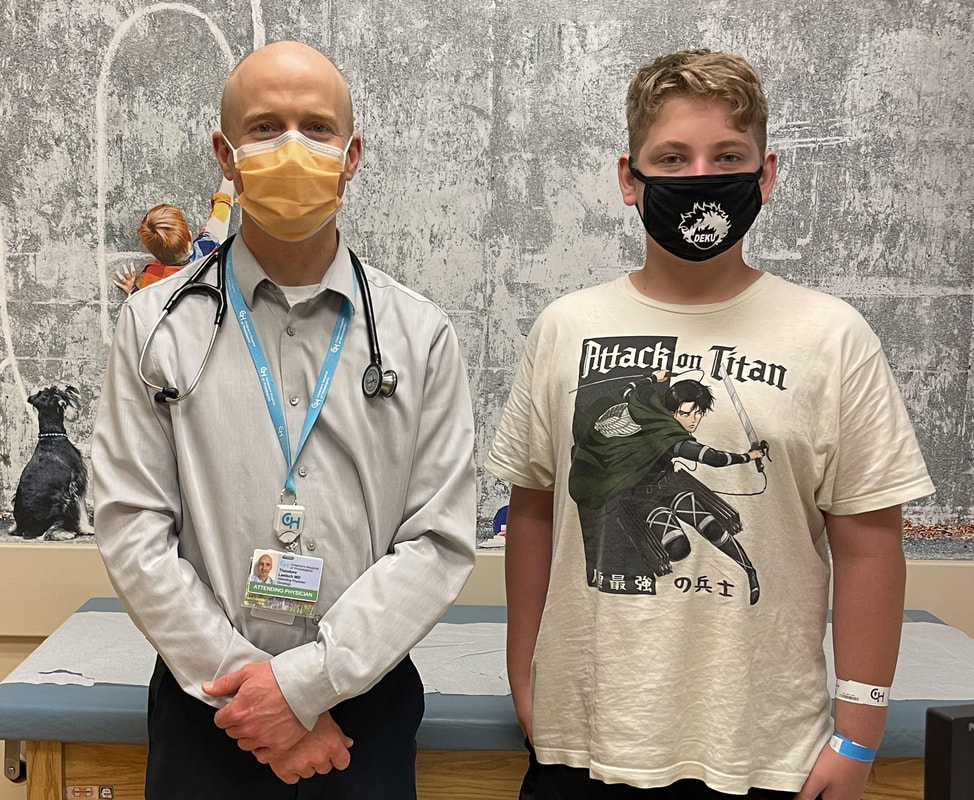

After many days of mother-son bonding in the hospital, and Doug driving 2 hours each way every 2 days so he could continue to work, pediatric oncologist Ted Laetsch, M.D. came into Brady’s room. He told them they’d received the more specialized testing results and that Brady had a very rare type of soft tissue tumor called a TRK-fusion positive spindle cell neoplasm. He quickly added, “The good news is that we have a study here that we think would be a solution for him.”

Two years of treatment

Brady stayed in the hospital for 21 days so that his doctors could make sure the treatment was working and his breathing was stable. Brady and his mom missed Brady’s sister’s wedding.

After he was able to go home, in addition to taking his pills at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. every day, Brady came to CHOP every month for blood work and periodic CT scans and MRIs.

After the first CT scan, they could see that the tumor in his throat was shrinking.

After many days of mother-son bonding in the hospital, and Doug driving 2 hours each way every 2 days so he could continue to work, pediatric oncologist Ted Laetsch, M.D. came into Brady’s room. He told them they’d received the more specialized testing results and that Brady had a very rare type of soft tissue tumor called a TRK-fusion positive spindle cell neoplasm. He quickly added, “The good news is that we have a study here that we think would be a solution for him.”

Two years of treatment

Brady stayed in the hospital for 21 days so that his doctors could make sure the treatment was working and his breathing was stable. Brady and his mom missed Brady’s sister’s wedding.

After he was able to go home, in addition to taking his pills at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. every day, Brady came to CHOP every month for blood work and periodic CT scans and MRIs.

After the first CT scan, they could see that the tumor in his throat was shrinking.

Dr. Laetsch said, “Brady’s response to larotrectinib was exactly what I’d hoped and what we’ve now seen in almost all patients like Brady. It started working almost immediately. Larotrectinib was designed to specifically treat TRK-fusion tumors, and leave the rest of the body alone as much as possible. It’s a great example of how precision medicine works, and I’m so grateful to COG for helping us get to this ground-breaking turning point.”

Seeing that larotrectinib was working helped Brady deal with minor side effects – weight gain and “chemo withdrawal pain.”

“About an hour to an hour and a half before taking his pill, his body would start to ache. It was kind of like the flu where it hurts to move, or be touched. But then, 30 to 45 minutes after taking his pill, the pain and sensitivity would go away,” said Stacy.

|

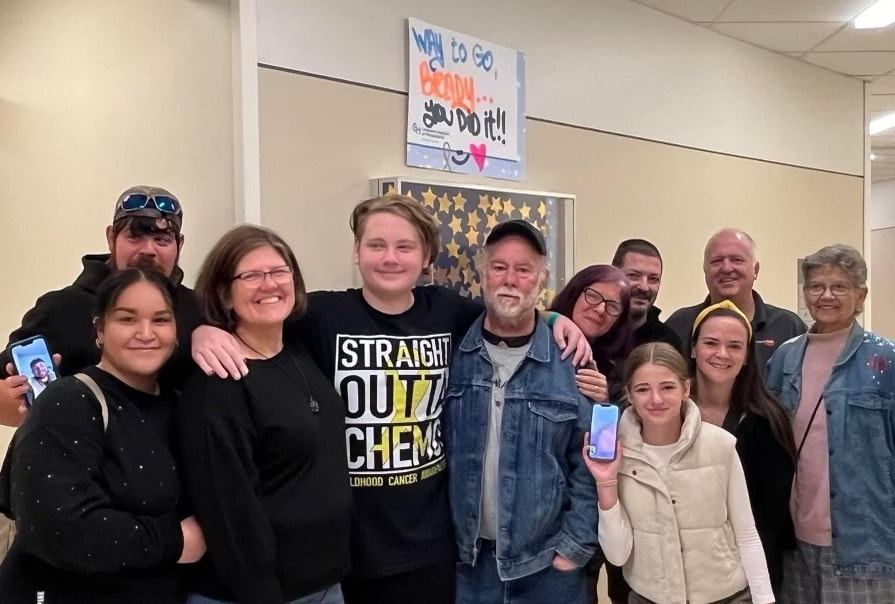

Grateful to be cancer-free

Brady and his parents will never know exactly how things would’ve been different if Brady had received traditional chemo. But they’re pretty sure Brady’s weight gain and withdrawal pain were the smaller price to pay. “With this trial, I honestly felt like Dr. Laetsch was saving my son’s life,” Stacy said. In October 2023, surrounded by his CHOP care team and holding the plastic anime sword that one of his favorite techs, Angel, gifted him, Brady “rang the bell,” a tradition at pediatric hospitals around the country. Ringing a giant bell announces to everyone that a child has finished their cancer treatment. He also added a star to the bulletin board of all the other children who were on the other side of treatment. |

Once the spotlight was off of him, Brady felt relief wash over him. Cancer-free, he could breathe deeply again – literally. While he will still need follow-up scans to make sure the cancer stays away, he can now turn his focus back to getting through school.

|

Post-treatment, Stacy is looking forward to having more time. She’s joined a book club, something that feels nice and “normal.”

Reflecting on the opportunity to participate in rare cancer research, Stacy gets choked up. “I am a million times grateful for all of the donors who helped make larotrectinib research possible and gave Brady the opportunity to get healthy and have a new life,” she said. |

Today, because of Brady and patients all across the country who participated in larotrectinib research, larotrectinib is now available as a standard treatment option for babies, kids and young adults with TRK-fusion tumors.

|

For Dr. Laetsch, Brady’s story fuels his motivation to continue to bring treatments that target tumors with specific genetic changes to more patients – as alternatives to more toxic ones. But mom Stacy sums it up best: “I think about Brady going to a job interview and being asked, 'What was a hurdle that you had to get over?" and he can answer, ‘Well, I beat cancer.’ And he can say that because he got the right study, the right medication, and the right team.” |